RedMonk.com published an article in February 2016 documenting some interesting stats around the "rise and rise" of a powerful asynchronous messaging technology called Apache Kafka.

If you're unfamiliar with Kafka, it's a scalable, fault-tolerant, publish-subscribe messaging system that enables you to build distributed applications and powers web-scale Internet companies such as LinkedIn, Twitter, AirBnB, and many others. Small-scale open-source projects come and go, but it seems Kafka has some really strong momentum behind it.

So what is the value of Kafka? Why is it suddenly so popular, and should you use it? I'll give you enough information in this article to answer these questions.

Even slow-to-evolve enterprises are noticing Kafka

RedMonk points out that Apache Kafka-related questions on StackOverflow, Apache Kafka trends on Google, and Kafka GitHub stars are all shooting up. In the graph below, you can see that GitHub interest has grown exponentially:

Apache Kafka GitHub Stars Growth

![]()

Image credit: RedMonk

This kind of technology is not only for Internet unicorns. I meet with enterprise architects every week, and I've noticed that Kafka has made a noticeable impact on typically slower-to-adopt, traditional enterprises as well. My colleagues in the enterprise and I are starting to see a common trend across companies of all backgrounds. They are starting to realize that to build the digital services that will disrupt and innovate, they need access to a wide stream of data, and that data must be integrated. However, the typical source of data—transactional data such as orders, inventory, and shopping carts — is being augmented with things such as page clicks, "likes," recommendations, and searches. All of this data is deeply important to understanding customers' behaviors and frictions, and it can feed a set of predictive analytics engines that can be the differentiator for companies. This is where Kafka comes in.

Kafka's origin story at LinkedIn

Kafka was developed around 2010 at LinkedIn by a team that included Jay Kreps, Jun Rao, and Neha Narkhede. The problem they originally set out to solve was low-latency ingestion of large amounts of event data from the LinkedIn website and infrastructure into a lambda architecture that harnessed Hadoop and real-time event processing systems. The key was the "real-time" processing. At the time, there weren't any solutions for this type of ingress for real-time applications.

There were good solutions for ingesting data into offline batch systems, but they exposed implementation details to downstream users and used a push model that could easily overwhelm a consumer. Also, they were not designed for the real-time use case.

Real-time systems such as the traditional messaging queues (think ActiveMQ, RabbitMQ, etc.) have great delivery guarantees and support things such as transactions, protocol mediation, and message consumption tracking, but they are overkill for the use case LinkedIn had in mind. Everyone (including LinkedIn) wants to build fancy machine-learning algorithms, but without the data, the algorithms are useless. Getting the data from source systems and reliably moving it around was very difficult, and existing batch-based solutions and enterprise messaging solutions did not solve the problem.

Kafka was developed to be the ingestion backbone for this type of use case. Back in 2011, Kafka was ingesting more than 1 billion events a day. Recently, LinkedIn has reported ingestion rates of 1 trillion messages a day. Let's take a deeper look at what Kafka is and how it is able to handle these use cases.

How does Kafka work?

Kafka looks and feels like a publish-subscribe system that can deliver in-order, persistent, scalable messaging. It has publishers, topics, and subscribers. It can also partition topics and enable massively parallel consumption. All messages written to Kafka are persisted and replicated to peer brokers for fault tolerance, and those messages stay around for a configurable period of time (i.e., 7 days, 30 days, etc.).

The key to Kafka is the log. Developers often get confused when first hearing about this "log," because we're used to understanding "logs" in terms of application logs. What we're talking about here, however, is the log data structure. The log is simply a time-ordered, append-only sequence of data inserts where the data can be anything (in Kafka, it's just an array of bytes). If this sounds like the basic data structure upon which a database is built, it is.

![]()

Image credit: Apache Kafka

Databases write change events to a log and derive the value of columns from that log. In Kafka, messages are written to a topic, which maintains this log (or multiple logs — one for each partition) from which subscribers can read and derive their own representations of the data (think materialized view).

For example, a "log" of the activity for a shopping cart could include "add item foo," "add item bar," "remove item foo," and "checkout." The log would present these facts to downstream systems. If a shopping cart service reads that log, it can derive the shopping cart objects that represent what's in the shopping cart: item "bar" and ready for checkout. Because Kafka can retain messages for a long time (or forever), applications can rewind to old positions in the log and reprocess. Think of the situation where you want to come up with a new application or new analytic algorithm (or change an existing one) and test it out against past events.

What Kafka doesn't do

Kafka can be very fast because it presents the log data structure as a first-class citizen. It's not a traditional message broker with lots of bells and whistles.

- Kafka does not have individual message IDs. Messages are simply addressed by their offset in the log.

- Kafka also does not track the consumers that a topic has or who has consumed what messages. All of that is left up to the consumers.

Because of those differences from traditional messaging brokers, Kafka can make optimizations.

- It lightens the load by not maintaining any indexes that record what messages it has. There is no random access — consumers just specify offsets and Kafka delivers the messages in order, starting with the offset.

- There are no deletes. Kafka keeps all parts of the log for the specified time.

- It can efficiently stream the messages to consumers using kernel-level IO and not buffering the messages in user space.

- It can leverage the operating system for file page caches and efficient writeback/writethrough to disk.

Kafka and big data at web-scale companies

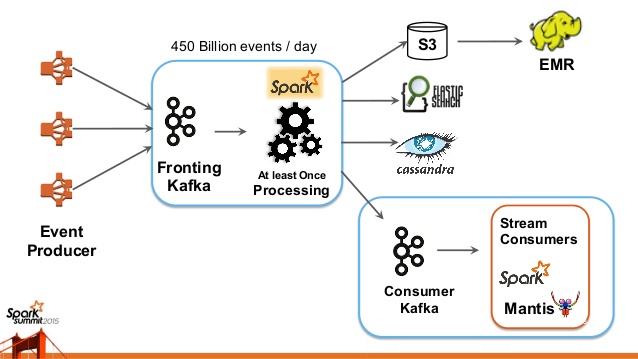

Because of these performance characteristics and its scalability, Kafka is used heavily in the big data space as a reliable way to ingest and move large amounts of data very quickly. For example, Netflix started out writing its own ingestion framework that dumped data into Amazon S3 and used Hadoop to run batch analytics of video streams, UI activities, performance events, and diagnostic events to help drive feedback about user experience. As the demand for real-time (sub-minute) analytics grew, Netflix moved to using Kafka as its primary backbone for ingestion via Java APIs or REST APIs. Netflix's system now supports ingestion of ~500 billion events per day (~1.3 PB data) and at peak up to ~8 million events per second. It has paired Kafka with streaming stacks like Apache Spark and Apache Samza to route data and load it into back-end data stores like ElasticSearch and Cassandra, as well as directly into real-time analytics engines.

Big Data ingestion at Netflix

Image credit: Netflix

This architecture is new alternative to the lambda architecture, and some are calling it the kappa architecture. Open-source developers are integrating Kafka with other interesting tools. One stack, called SMACK, combines Apache Spark, Apache Mesos, Akka, Cassandra, and Kafka to implement a type of CQRS (command query responsibility separation). This stack benefits from powerful ingestion (Kafka), back-end storage for write-intensive apps (Cassandra), and replication to a more query-intensive set of apps (Cassandra again). All of this can be managed with a resource/cluster management solution such as Apache Mesos.

How Kafka supports microservices

As powerful and popular as Kafka is for big data ingestion, the "log" data structure has interesting implications for applications built around the Internet of Things, microservices, and cloud-native architectures in general. Domain-driven design concepts like CQRS and event sourcing are powerful mechanisms for implementing scalable microservices, and Kafka can provide the backing store for these concepts. Event sourcing applications that generate a lot of events can be difficult to implement with traditional databases, and an additional feature in Kafka called "log compaction" can preserve events for the lifetime of the app. Basically, with log compaction, instead of discarding the log at preconfigured time intervals (7 days, 30 days, etc.), Kafka can keep the entire set of recent events around for all the keys in the set. This helps make the application very loosely coupled, because it can lose or discard logs and just restore the domain state from a log of preserved events.

How does Kafka compare to traditional messaging competitors?

Just as the evolution of the database from RDBMS to specialized stores has led to efficient technology for the problems that need it, messaging systems have evolved from the "one size fits all" message queues to more nuanced implementations (or assumptions) for certain classes of problems. Both Kafka and traditional messaging have their place.

Traditional message brokers allow you to keep consumers fairly simple in terms of reliable messaging guarantees. The broker (JMS, AMQP, or whatever) tracks what messages have been acknowledged by the consumer and can help a lot when order processing guarantees are required and messages must not be missed. Traditional brokers typically implement multiple protocols (e.g., Apache ActiveMQ implements AMQP, MQTT, STOMP, and others) to be used as a bridge for components that use different protocols. Additional functionalities such as message TTLs, non-persistent messaging, request-response messaging, correlation ID selectors, etc. are all perfectly valid messaging use cases where Kafka would not be a good fit.

Should you use Kafka?

The answer will always depend on what your use case is. Kafka fits a class of problem that a lot of web-scale companies and enterprises have, but just as the traditional message broker is not a one size fits all, neither is Kafka. If you're looking to build a set of resilient data services and applications, Kafka can serve as the source of truth by collecting and keeping all of the "facts" or "events" for a system.

In the end, you'll have to consider the trade-offs and drawbacks. If you think you can benefit from having multiple publish/subscribe and queueing tools, it might be worth considering.

Keep learning

Take a deep dive into the state of quality with TechBeacon's Guide. Plus: Download the free World Quality Report 2022-23.

Put performance engineering into practice with these top 10 performance engineering techniques that work.

Find to tools you need with TechBeacon's Buyer's Guide for Selecting Software Test Automation Tools.

Discover best practices for reducing software defects with TechBeacon's Guide.

- Take your testing career to the next level. TechBeacon's Careers Topic Center provides expert advice to prepare you for your next move.